Introduction

Multinational joint stock companies are among the most influential institutions today. One of the world’s first multinational companies, the British East India Company (EIC), accomplished the biggest takeover in history, the subjugation of an entire subcontinent of around 200 million people. The (true) story of the EIC and its relationship with the British Parliament is one of the earliest examples of how corporations can influence governments and how governments can influence corporations to become proxies for them overseas. The EIC’s literal takeover of the Indian subcontinent began as a part of a proxy conflict with France that would start a series of chain reactions in Europe and America. It was a rivalry that could become a precursor to what may come in the not-too-distant future. Today, Elon Musk is leading the drive for private companies in outer space-related industries, just as the founders of the EIC took the initiative to profit from long-distance trade.

The Innovation of Joint Stock Companies

Multinational joint stock companies are an early 17th-century Anglo-Dutch innovation. The Protestant Reformation in England and the Netherlands cut them off from the lucrative spice trade with the East Indies, then dominated by Portugal,forcing them to find their means of trading with Asia. Unlike Spain and Portugal, the English and Dutch governments did not have access to vast deposits of precious metals to fund government monopolies on long-distance trade. So, they had to leave it to private monopolies and open it to private investors. Arguably, the first joint stock company was the Muscovy Company, founded in England in 1555, with a trade monopoly between England and Russia. The British East India Company was founded in 1600 by a group of English privateers who sought and gained a royal charter for a monopoly on Asian trade. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) was founded in 1602.

At first, the EIC was not a success, in part because of the limited number of investors that the company could attract. The Dutch had similar issues but devised an ingenious solution: the stock market. Joint stock companies made it possible to profit from investing in the company without being directly involved. Still, the East India Company went even further by allowing company shares to be bought and sold, providing more incentive to invest in the EIC company by trading stocks. This superior means of funding helped the VOC beat the EIC at gaining a monopoly on the spice trade, which was concentrated in the islands of modern-day Indonesia. Fortunately for the EIC, there was another untapped market of “exotic” commodities that Europeans craved: textiles.

India: the Manufacturing Giant of the Pre-Industrial Age

India was home to the world’s largest textile manufacturers. Many words and innovations associated with textiles, such as pajamas or cashmere, have Indian origins. For much of the 16th and 17th centuries, England was an underdeveloped nation by Indian standards. The Mughal Empire contained at least 150 million inhabitants, the world’s largest industrial capacity, armies, and cities. The idea that a small England could ever conquer the subcontinent with over 20 times its population was ludicrous. Instead, the EIC sought to establish trading relations with the Mughals, which it managed to do so successfully. By the mid-17thcentury, England had normalized relations with Spain, giving them access, via trade, to precious metals from the Americas, especially silver. Silver was the primary metal in coinage production worldwide, making it the closest thing to a universal currency. The Mughals and other Indian princes were happy to allow European trade for the silver and gold it brought them.

The most crucial British factory (trading post) was founded in what would become Bombay on the western coast of India in 1662. Within thirty years, the “factory” became a trading settlement of 60 thousand people. The EIC reaped unprecedented profits from its India trade, and its directors gradually realized they could use the value of its stock shares (an innovation they recently copied from the Dutch) to, in essence, bribe parliamentarians. The world’s first insider trading scandal involved the EIC director Sir Joseph Child and the King’s Privy Council President Thomas Osborn in 1695, though King William III prevented any legal action from being taken. Child arguably pioneered the art of corporate lobbying. Child also made the bad decision to resist the Mughal empire’s increasingly capricious taxes, which destroyed several English trading posts on the western coast of India. The company decided to compensate by building an additional trading post on the eastern coast of India. The site chosen was in India’s most productive province, Bengal. The settlement around the “factory” became known as Calcutta.

India: a House Divided Against Itself, Ripe for a Takover

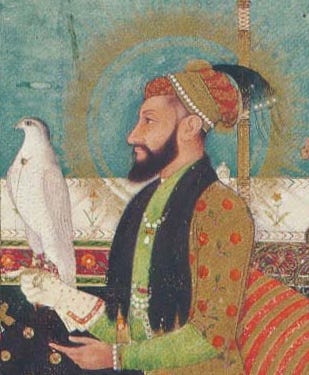

In 1707, the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb died, and the Mughal Empire began to fracture. Aurangzeb is probably the most controversial ruler in Indian History. Traditionally, Aurangzeb has been portrayed by British and post-Independence Indian historians as a Sunni fundamentalist bigot who tore India between Muslims and Hindus. More recent, scholarship has downplayed some of the more extreme allegations against him. Ultimately, I believe Aurangzeb’s biggest fault is that he was a warmonger who bled the Mughal Empire dry in fruitless wars (against Muslims and Hindus alike) during his 40-year reign. A series of dynastic civil wars, raids by Mathra insurgents, and the sack of Delhi by Nader Shah in 1757 resulted in a complete breakdown of imperial power. Provincial governors called Nawabs now exerted de facto independence. The balkanization of India was one of the most critical factors in the British conquest of the subcontinent.

The EIC was fortunate to have established a trading post at the right place and time. Bengal was one of the former provinces that became a de-facto independent state. Under the rule of Alaverdi Khan from 1740-1751, Bengal became the most prosperous province in India. The rapid growth of Calcutta is linked to the flow of trade in and out of Bengal. Precious metals, especially silver, were exported to India to pay for Indian commodities, as they had since antiquity. The textile trade prompted the EIC to ship large amounts of silver to Bengal in return for textiles, pepper, saltpeter (a vital indigent in gunpowder), and other Indian commodities. The influx of silver helped fuel indigenous commerce among Bengali bankers and merchants who also helped fund EIC operations. Naturally, the EIC profits garnered the attention of England’s great European rival, France. Franco-English rivalry would be the catalyst for the largest takeover in history.

The Sepoys

The immensely-profitable Indian trade attracted the attention of France, England’s archrival in Europe, and the French founded the Compagnie des Indes to trade with India. This campaign established several trading posts in Southern India. When war broke out between France and England in India in 1744, Joseph Francois Dupleix, director of the French settlement of Pondicherry, started recruiting Indigenous men into the (French) companies’ private armies and turning them into a European-style army. The sepoys were born and soon proved their effectiveness. A force of 700 French sepoys defeated 10,000 Mughal troops at the Battle of Paradis in 1746, using new 18th-century weaponry and combat tactics combining canister shot, volley fire, bayonets, and mobile field artillery. Indian civilization was already familiar with gunpowder and metallurgy, so it was possible to manufacture modern weapons indigenously.

The sepoys had many advantages. Indigenous troops were far less susceptible to local disease than Europeans, and the local labor pool was abundant. However, the French could not use their innovation to its full potential in large part because France's financial institutions were underdeveloped compared to Great Britain’s. For example, the King of France monopolized shares in the Compagnie, and other aristocrats were more interested in politics than trade. The system also meant that the Compagnie could not raise revenue from private sources like the EIC could, making it almost always short of funds. The French in India never had enough capital to raise an army big enough to dislodge the EIC. Conversely, the British would raise enough capital for an army that would dislodge the French and eventually subdue the entire subcontinent.

The World’s First Mega Bailout

In 1756, Alaverdi Khan died, and his successor, Siraj ud-Daula, was far less qualified. The new, untested Nawab of Bengal, presumably under the influence of the French, attacked Calcutta and sacked it. The sacking of Calcutta had a detrimental effect on the Bengali economy by cutting off the province's source of silver. Siraj further alienated the bankers and merchants that sustained the Bengali economy with rapacious tax demands. Robert Clive was given the task of retaking Calcutta. Clive knew he had to imitate the French method of raising indigenous troops to defeat the Nawab. Clive’s sepoy army, financed in part by Indian merchant allies, defeated the armies of the Nawab and his French allies. Later, in 1765, Clive decided the Company should rule Bengal and obtained a Diwan or mandate from the powerless Mughal Emperor Shah Alem. In a decade, the EIC transformed from a trading Company with a few trading settlements into a significant territorial power.

Bengal would become the EIC’s gateway to conquer all of India, but first, they had to preserve it. The Company almost ruined itself after acquiring Bengal in 1765 because the EIC was unprepared to govern such a large territory. Previously, Europeans traded for goods with precious metals, particularly silver, which fueled the Indian economy. The EIC tried to use Bengali tax revenues to fund the purchase of goods, but the loss of silver imports led to rampant inflation. With no legal system to hold them accountable, the EIC’s personnel in Bengali became exceedingly rapacious and corrupt. Around this time, the word loot, a Hindi slang for plunder, entered the English language. A prolonged drought led to a massive famine in Bengal, exacerbated by the EIC’s rapaciousness and mismanagement. From London’s point of view, the worst part was that news of the disaster led to a plummet in the EIC’s stock prices, ruining many, including parliamentarians.

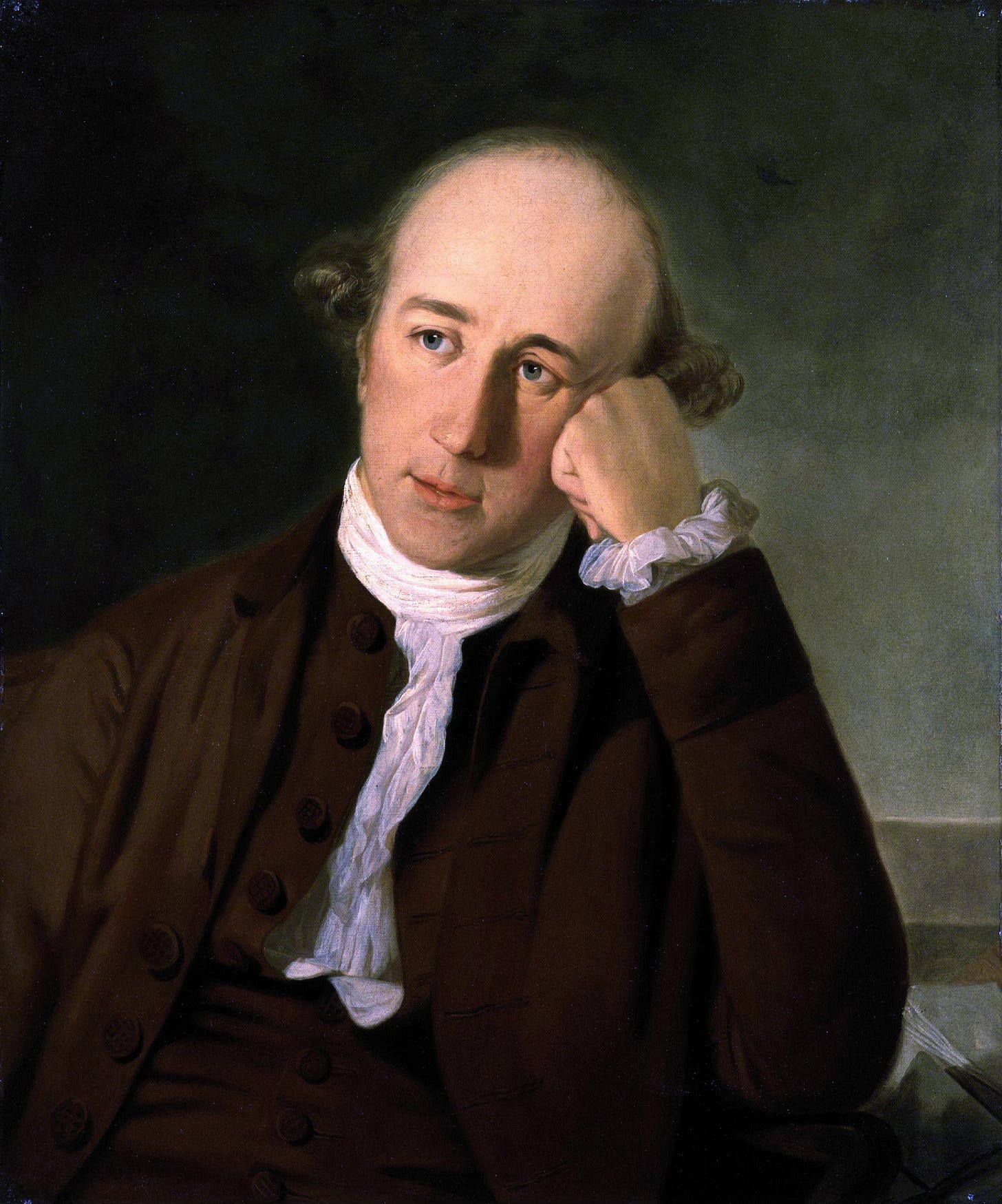

The “Bengali bubble” prompted the British Parliament to launch the world's first-ever corporate investigation in 1772. Despite calls to revoke the Company's monopoly and bring Bengal under direct British rule, Parliament decided instead on a compromise. The Regulating Act of 1773 stipulated that a governor-general appointed by the British government would oversee the EIC possessions. The first governor-general of Bengal was Warren Hastings. Hasting had worked in India for decades and witnessed how the EIC almost destroyed its golden goose. He knew hot to fix it. Under Hastings, the EIC resumed importing silver bullion to pay for Indian products, which solved the currency crisis that had paralyzed the Bengali economy. By 1790, the Calcutta mint produced silver and gold coins at a rate of Rs 2.5 million a year. As the drought receded and Hastings’s reforms bore fruit, Bengal became a breadbasket that could feed the province and the EIC’s armies. The province’s riches enabled the formation of a large sepoy army equipped with an indigenous armaments industry. This was done at little to no cost to the British taxpayer, though at considerable costs to the Bengali taxpayer. Hastings saved the British Raj in its cradle through Machiavellian machinations that splintered a coalition of Indian princes that nearly drove the company out of India in 1780.

While Hastings consolidated the EIC’s hold over Bengal, the British Empire lost its thirteen American colonies to an internal revolt and French intervention. Hastings’s political rivals blamed him for all the faults in the company rule and organized his impeachment in 1786. Hastings was replaced as Governor-General by Charles Cornwallis. Cornwallis enacted further reforms to prevent a repeat of the American War of Independence in India. Cornwallis probably believed, with some justification, that one of the reasons for the American Revolution was the lack of a large landlord class with ties to the crown. Cornwallis launched a land reform program to buy or confiscate the old Mughal aristocracy’s lands and resell them to a new landlord class known as Zamindars. If a Zamindar failed to meet his tax quota in the form of cash or crops, the estate would be confiscated and resold to the highest bidder. The result was a significant increase in land tax revenue from 2 million under the Nawab to 5 million under the EIC by 1793, though Bengali farmers suffered from increased tax burdens.

No Unified Resistance

Cornwallis recognized that the most direct threat to the British hold on India was Tipu Sultan, ruler of Mysore. Tipu Sultan was, in many ways, a remarkable ruler who modernized his kingdom and armies along European lines but who was also highly flawed. Tipu Sultan made himself vulnerable by making enemies of other Indian states, which pushed them to align with Cornwallis. Tipu had gambled on receiving French support to counter the EIC dominance at sea, but unfortunately for him, the French Revolution had begun, and no support was forthcoming. Despite Tipu Sultan’s ingenious tactics and fortifications, the combined forces of the EIC and their Indian allies were too much. The third Anglo-Mysore conflict (1790-1792) ended in a decisive English victory. Cornwallis added 20 million people to British rule, ten times the amount he lost in America. Tipu lost almost half his Kingdom.

With Mysore bloodied, only the Mathra confederacy could stop the company, but like the Mughals, it fatally weakened itself in the Civil War. When Nana Phadnavis, the leader of the Maratha Confederacy, died in 1800, the Maratha Confederacy all but disintegrated into rival factions. From time immemorial, Indian states have been prone to civil war and interstate conflict. The EIC did not suffer repeated civil wars like the Mughal Empire and the Maratha Confederacy. It was never in any danger of fracturing. For all these reasons, Indian merchants and bankers increasingly threw in their lot with the EIC. Backing the EIC was more of a rejection of rule by the princes. Gradually, Indian princes were drawn into British hegemony.

India Subdued

The arrival of Richard Wellesley in 1798 signaled a more cooperative approach to the Indian princes. Previously, merchants seeking profit managed the Company, which helped them “bond” with the Indian mercantile class, but starting with Cornwallis, conservative aristocrats were now leading the Company. Richard Wellesley and his younger brother Arthur, the future Duke of Wellington who accompanied him, were both arch-conservatives who could relate to their Indian counterparts’ desire to maintain their dominance within the status quo, which gave Indian princes incentive to accept British hegemony. Tipu Sultan was fatally weakened, and the Maratha Confederacy unraveled; Hyderabad threw in its lot with the British and helped them defeat Tipu Sultan; in return, the Nobonas of Hyderabad were allowed to maintain a degree of autonomy under British hegemony.

In 1798, Napoleon, who harbored a dream of an French empire in Asia, wrote a letter to Tipu from Egypt implying that he was preparing to sail to India with a large army. British agents intercepted the letter in the port of Jeddah. Perhaps Wellesley had gotten wind of Napoleon’s offer. Wellesley wrote a letter to Tipu, informing him of the French defeat at the Battle of the Nile and implying he should become a Company protectorate, which Tipu refused. Wellesley probably already decided to make an example of Tipu by destroying him to deter any other prince from aligning with any European power besides the Company, especially the French. Wellesley raised the equivalent of RS10 (130 million today) from Bengali bankers to fund the war of conquest against Tipu Sultan. Despite Tipi’s record as a skilled military commander, they knew which side to put their money on. Tipu was killed in 1798 when his capital fell to the forces of Arthur Wellesley, future Duke of Wellington.

The last major power on the subcontinent was the Maratha confederacy. Some Maratha lords saw the Company as a possible ally against rivals within the Confederacy. Baji Rao, the nominal leader of the Confederacy, who lost his position to a rival warlord, allied with the Company to regain his lands in return for acknowledging Company overlordship. Arthur Wellesley (he wasn’t Duke of Wellington until 1814), promoted to general following Tipi’s defeat, underestimated the Marathas. The Marathas also invested in European-style armies and weaponry, which their commanders adapted to suit Indian conditions. Maratha artillery fire nearly killed Arthur Wellesley at the Battle of Assaye. Just before this battle, Arthur Wellesley’s artillery got stuck in the mud, delaying his army and giving the Maratha time to organize an effective defense. Though Arthur Wellesley won the battle, it was a pyrrhic victory, costing him around half his army and halting his advance into Maratha territory.

Whenever the Indian princes were significantly unified, they could keep the Company at bay. Arthur Wellesley’s near-defeat at Assaye shows how the Indian princes effectively used European-style weaponry and innovative tactics to suit Indian conditions. Even Indian sepoys fighting under the princes displayed extraordinary resolve and ability, enough to give the future Duke of Wellington a run for his money. However, as the Company and its Indian “investors” knew from experience, Indian coalitions never lasted long. Even if they managed to hold the Company at bay in the short term, they would always succumb to factional infighting soon afterward, so an Indian coalition was also a bad long-term investment.

The Company's economic, financial, and, by extension, military resources were enough to wage war on two fronts. While Arthur Wellesley was fighting in the Maratha heartland, another British general, Gerard Lake (a veteran of Yorktown), was fighting the Maratha for control of Northern India. Lake had the advantage of facing less talented enemy commanders. Most elite Maratha commanders were away fighting in the Maratha heartland, leaving Northern India to less capable commanders and French mercenaries. Mercenaries tend to get paid only if they are on the winning side. The Marathas’ fragile financial situation is reflected in its failure to provide its French-trained sepoy infantry with regular payment, leading many to desert. Lake enticed the mercenaries into switching sides, weakening the Maratha forces in Northern India. The Company was able to pay their sepoys regularly, partly thanks to remittances from indigenous banking firms who cast in their lot with the Company. Lake gained control of Delhi and the blind, powerless Mughal Emperor Shah Alam. In hindsight, this was a hugely pivotal moment in Indian history that marked the end of over 800 years of minority Muslim rule.

Despite the Company's advantages, the campaign against the Marathas in Northern India was brutal, with many losses on both sides. The Battle of Delhi on September 11, 1803, was decisive in India and Indian history. It was the last time British and French officers fought one another in Asia, and the latter surrendered the keys to the city. The EIC had established hegemony over India and, with it, a period of relative peace and stability by Indian standards. Ultimately, the Companies' Indian “investors” got what they wanted. Over nine years, Richard Wellesley conquered most of peninsular India, more territory than Napoleon conquered (and lost) in Europe.

End of the Company and Beginning of the Raj

The British Empire now had around 200 million subjects, more than Europe's total population. However, Wellesley nearly drove the Company to the brink of bankruptcy. From a purely financial perspective, Wellesley’s governorship was catastrophic. The EIC board of directors managed to lobby Parliament for Richard Wellesley’s dismissal in 1805. Great Britain was fighting Napoleon and needed its best officers back home. The EIC was increasingly becoming an extension of the British government, acting in the interest of Great Britain instead of company profit. If Indian merchants and bankers resented the EIC’s trade monopoly, they found an unlikely ally in Liverpool merchants and industrialists who successfully lobbied Parliament to revoke the EIC’s monopoly on trade with India in 1813.

Napoleon's defeat in 1815 marked the end of the Anglo-French rivalry in India. Gradually, the company subdued the rest of the Indian subcontinent. While the Company's power in India grew, its power in England faded. In 1833, Parliament passed a measure that removed the Company's right to trade, turning it into a wholly owned government branch. The final blow to the Company was when elements in its army revolted in 1857 in what would become known as the Sepoy Mutiny. The Sepoy Mutiny had a variety of causes besides allegedly violating Muslim and Hindu sensibilities by using animal fat to grease cartridge rounds. After the revolt was suppressed, the British formally dissolved the Company with the British India Act of 1858, dethroning the last Mughal Emperor and proclaiming Queen Victoria empress of all India. The British ruled India until 1947. Ironically, France held on to a few enclaves in India, including Pondichéry, until 1952, outlasting the British.

Conclusion

The success of multinational joint stock companies is rooted in their ability to raise money. Wars are expensive, and states need to borrow money to fund it. Bond markets preceded stock markets. Today, both governments and companies use bonds to raise money. The EIC was both a company and a government. They raised enough money to fund the conquest of a subcontinent with at least 200 million people. Much of the money that funded the conquest of India came from indigenous sources, which minimized the cost to the English taxpayer. The French East India Company failed primarily because its financial institutions were underdeveloped. Fear of French influence in India helped prompt English leaders like Clive and Weasley to launch wars of conquest in India to prevent France from doing the same. They were able to do so thanks to financial resources at their disposal, which allowed them to raise Indigenous armies. The sepoys started as mercenaries for a trading company and became a national army. Multinational companies today occasionally employ PMCs whenever they operate in places where local governments cannot guarantee their safety, like guarding oil facilities in the Niger Delta, for example.

Mega corporations with private armies are a popular theme in science fiction, especially space operas. Even theoretically, long-distance space travel is very loosely comparable to crossing the oceans before the 18th century, with vast distances, enormous expenses, high risks, and years before seeing a profit. Controversial billionaire Elon Musk, who is leading the drive for the private spacefaring industry, is loosely comparable to the founders of the British and Dutch EIC, who influenced their respective governments into granting them a monopoly on Asian trade.

Amazing Article.

Thank you