The life of Nader Shah resembles a cross between Napoleon and McBeth. Nader rose from humble beginnings as an ordinary soldier on the frontiers of 18th-century Persia to become the Shah of Persia. Had it not been for Nader Shah, Persia might have been carved up as Poland was in the same century or colonized as India was a century later. However, his life ended in a horrific, almost Shakespearian manner. The ultimate tragedy of Nader Shah is that though he saved Persia, he left it worse off than when he found it. Nader’s life, legacy and the circumstances surrounding his demise cannot be attributed to the Islamic world he was raised in. Politics and war are practical fields. Nader was, for most of his life, a practical man. Even practical men can be corrupted if left unchecked, as was the case for Nader Shah. Towards the end of his life, Nader became increasingly paranoid and cruel, almost to the point of insanity. Human cruelty is universal; it takes different forms from place to place, culture to culture, and society to society. Societies and civilizations have developed traditions, values, and, most importantly, institutions to protect themselves from excess and neglect; The life of Nader Shah is an example of how great people be undone by their own excess. Perhaps Nader Shah’s biggest failure was that he failed to establish long-lasting institutions to secure his legacy. When power becomes an end onto itself, there is tyranny and tragedy.

The Man and his world

The date of Nader Shah’s birth is uncertain, but his biographer, Micheal Axworthy, names the most likely date as August 6th, 1698. Nader was born in the Persian frontier village of Dastgerd, in what is now northeastern Iran. Nader’s family, like most in the region, were predominantly pastoralists. Nader’s father died when he was young, forcing the family into poverty. Nader would have had to struggle to survive and be determined to prove himself from an early age in an already rugged land. Nader’s upbringing as a fatherless nomad on the frontiers of civilization might be why he usually disdained people with sedentary lifestyles like city dwellers and farmers. At the age of fifteen, he joined the retinue of a local governor and soon distinguished himself as a fighter when dealing with raiders. Nader, typical of someone in his circumstances, would not have received any formal education outside of the military sphere. Nader’s upbringing may have helped forge him into a brilliant military leader, but it also made him somewhat detached from those who lived a more sedentary lifestyle, like farmers and urbanites, which would have dire consequences later.

Nader would have had other reasons to disdain more “peaceful” ways of life. The court of the Safavid Shah at Ishan was ripe with corruption and incompetence. The Safavid dynasty was founded in the 16th century by a confederacy of Shite Muslim tribes. According to 15th-century Arab historian Ibn Khaldun, a dynasty's strength rested in group cohesion fostered by a life of hardship in remote mountains and deserts. This cohesion made them a fearsome force and empire builders, but over time, the rulers would gradually distance themselves from their nomadic origins to better integrate themselves into the urban population. Eventually, it reached the point where ostentation became a means unto itself, alienating their former supporters. Near the end, the dynasty loses itself in vice, vanity-building projects, and corruption, resulting in it being conquered by another group of nomads, and the cycle repeats itself. That depiction would suit the Safavid dynasty in Nader’s time. Curiously, it might have also impacted his views on religion. Under Safavid rule, Persia/Iran became a predominantly Shia country. Government policy occasionally shifted from periods of tolerance to Shia supremacy depending on the whims of the Shah or court factions. Though Nader was born a Shite, he was personally irreligious. Nader grew up alongside Sunni tribes, who were often driven to revolt in response to persecutions by the Safavids, and the urbanized Shite clergy may have mistreated his family. Nader's irreligiously would perhaps serve as a warning to the current rulers of Iran that their theocracy may end up discrediting religion overall.

Shah Soltan Hosein’s (reigned 1694-1722) upbringing and personality were the antithesis of Nader’s. Born and raised in the harem’s relative comfort, he was chosen as crown prince at the urging of court officials who believed he could be controlled. Shah Soltan Hossein was, by all accounts, well-meaning and gentle, with an aversion to bloodshed. He was also indecisive, passive, inconsistent, indulgent, inept, and a terrible judge of character. All these characteristics made Shah Soltan Hossein the worst man to put at the helm of an autocracy in crisis. Besides rampant corruption, there was famine, plague, banditry, domestic revolts, and incursions from other nomadic tribes. In 1722, a successful revolt by Afghan tribes in the then Persian-ruled Kandahar led to an invasion of Persia itself; the Afghans defeated the Safavid army and besieged the capital of Isfahan until the Shah was forced to surrender. These disasters were caused in massive part by the incompetence and corruption of the Safavid court. Subsequently, a power vacuum emerged that drew Ottoman, Russian, and others to invade to feast on Persia’s corpse. They would have almost certainly succeeded if not for Nader Shah.

Rise from obscurity out of the chaos.

For Nader, the collapse of the Safavid dynasty was an opportunity to rise to previously unimaginable heights, much like the French Revolution for Napoleon. In response to the collapse of the Safavid central authority, many governors and tribal leaders became de-facto independent warlords. Nader became the “Governor” or warlord of Khorasan (modern-day Northwestern Iran and southern Turkmenistan). Nader no doubt committed many betrayals and other “crimes” during his rise, but he had to survive. Nonetheless, his actions must have taken a psychological toll, and there is a limit to how much a human being can take. For example, The leader of the Afghan invasion, Mahmud, would reach his limit soon. Mahmud reached the pinnacle of his power when he took Isfahan in 1722; he committed many betrayals and brutality during his rise to power, and it would drive him insane as soon as things started to go wrong. Though Mahmud had taken the capital of Persia, only a tiny portion of the Safavid domain was under his control. The Afghans were homesick and deeply unpopular with the Persian population and began to desert. Mahmud slipped deeper into paranoia and ordered the massacre of the Safavid princes, including children; even by the standards of the time, this was considered unduly cruel. Mahmud was deposed and executed in a coup uncastrated by his generals. Mahmud’s rise and fall would be the precursor to Nader’s fall from grace.

Before the fall of Isham, one of Shah Hossein’s sons, Tahmasp, escaped and was sent to rally reinforcements from the provinces with little to no success. Tahmasp eventually came to Nader, who was by this time the leading warlord in Persia. As every other warlord would have, Nader used Tahmasp to legitimize his rise to power. In Tahmasp’s name, Nader raised enough men and money to build up his power base, turn back the Ottoman invasion of the Persian heartland, and ultimately retake Isham. Shah Hossein was executed by the Afghans who occupied Isham and Tahmasp proved himself to be as incompetent as his father and prone to alcoholism (the Islamic ban on the consumption of alcohol was usually ignored). When Nader’s forces drove the Afghans out of Isham in December 1729, he obtained the right to levy taxes from Tashmasp. The right to levy taxes and the ability to collect taxes is the foundation of state power, as it is the means to pay and supply the army to enforce its rule. Nader’s power base was his army; he always needed money and would resort to anything to get it. Tax collection was always at the center of Nader’s nonmilitary affairs and became increasingly rapacious as time went on.

Warfare in the Middle East and Central Asia

Warfare in the Middle East was very different from Europe at the time. Military thinking in Europe emerged from the idea of frontal assaults, born out of centuries of warfare with heavily armored knights and later by units of musket-armed infantry firing in volleys. On the other hand, warfare in the Orient evolved around centuries of war, being conducted primarily by horse-mounted archers, emphasizing outflanking the enemy rather than charging head-on. Hence, Asian muskets did not have bayonets since the bayonet was invented as an anti-carvery weapon, and mele carvery charges were not standard in Central Asia. Islamic warfare and civilization were different from Europe but far from primitive. European warfare was, in many ways, gradually becoming eastern-like. Austria and Russia’s many wars with the Ottoman Empire inclined them to adopt effective eastern-style tactics, such as outflanking the enemy and weaponry (the saber was an Islamic invention), which in turn inclined their European foes, France, Prussia, and England to do the same. Napoleon and the Duke of Wellington, who served in Egypt and India, respectively, both used Eastern-style tactics.

The precise details of training and actual battle in what is now the Middle East and India are not widely known. There are no equivalents of drilling manuals or memoirs. This is partially due to the gap between the literati and the warrior elite, who frowned on the other’s profession. Most of the warrior class, like Nader, probably did not want their methods to be well known for fear that their enemies could use them against them. Keeping their methods unrecorded might have made sense in the short term, but in the long term, it’s probably one of the reasons why Nader’s innovations failed to take hold. What is known is that firearms were not as widely used in Central Asia as they were in Europe at the time, in part because of the emphasis on fighting from horseback. It was challenging to load a musket on horseback. Since antiquity, Persian armies consisted of levies that were raised as soon as war began and disbanded as soon as the fighting ended, which made it impractical to equip and train large amounts of troops in firearms. Firearms were typically restricted to small numbers of elite musketeers, as in Europe during the early 17th century. Middle Eastern and Indian musketeers typically did not fire in volleys like Europeans. Asian muskets were typically heavier and longer raged than their European equivalents. Asian musketeers, unlike their European counterparts, typically had powered horns to feed the muskets with gunpowder; they could use it to adjust the firing range. Heavy Artillery was also less used; in Nader’s case, he preferred to operate light swivel guns called “zamburak” that could be mounted on camels and small numbers of heavy artillery.

Nader revolutionized warfare in central Asia by making his army professional and firearm-oriented. Accounts by European visitors spoke highly of Nader’s training methods, his officers' meritocracy, and his troops' efficiency and discipline; for example, they did not loot in the heat of battle. Nader relied heavily on “mounted infantry,” or units that traveled on horseback but dismounted in battle, which gave much more mobility without sacrificing firepower. Manufacturing firearms and training men to use them effectively is time-consuming and expensive. Nader could not allow his trained troops to disband and disperse, taking their expensive firearms with them, so they had to be constantly fed, paid, and well-supplied, which was extremely expensive. In Europe, states tackled the problem of maintaining expensive standing armies and navies with innovations like meritocracy in civil service, promoting economic development, issuing government bonds, and encouraging newer, more efficient means of farming, transport, commerce, and industry. Nader’s army could have been the basis for the same in Persia, but tragically for Persia, though Nader was very forward-thinking in military matters, his economic views were close to Septimius Severus’s “Enrich the Soldiery. Ignore everything else.” approach. During the time of Tamerlane, Nader’s idol, in 14th-century armies primarily consisted of hours-mounted archers who could live off the land and rely on tribute from urbanites, but that was unsustainable in an era of gunpowder warfare, which Nader tried to compensate by relying on loot. Instead of cultivating the economy, Nader sought to exploit it no matter how much to keep his army supplied. In time, this would have disastrous consequences for himself and Persia.

The Ascension

Two instances illustrate Nader’s personality at this point. Nader once had an officer who defeated the enemy executed for not informing him that he had encountered the enemy. It might sound unduly harsh, but raw intelligence is vital in battle; not being informed could lead to disaster. Nader had to ensure he was always well informed and teach his officers the consequences of not keeping him informed. By all accounts, his officers got the message, and none were executed for that reason afterward. In 1732, Nader decided to depose Shah Tahamship. Nader arranged for Tahamship to appear publicly drunk and exposing his drunkenness to the whole court, blaming them for getting the Shah drunk; they defended themselves by blaming Shah’s shortcomings, which provided Nader with a pretext for deposing Tahamship in favor of the latter’s infant son with himself as regent. What’s noticeable is that the coup was bloodless. Most usurpers or conquerors, like Mahmud, would have killed the preceding Shah, his family, and his courtiers out of paranoia and personal insecurity. However, Nader did not because, politically, he still needed the Safavid name to rule. Psychologically, his self-confidence was strong enough that he did not need to impress himself or anyone else with bloodshed. At this point in his life, Nader, very wisely, resorted to bloodshed only out of necessity.

Nader had successfully driven the Afghans out of Eastern Persia, but the Ottomans controlled large amounts of Persian territory in the West. Nader decided, in 1732, it was time to drive them out. He intended to invade Ottoman-controlled Iraq to use as leverage for negotiations with the Ottoman court in Istanbul. Nader and his “new model army” had a track record of success, so he felt overconfident. Nader made several tactical and strategic errors while on the campaign, such as dividing his forces, bringing in enough artillery for the siege, and mistakenly believing that the campaign would be short. Nader did not bring enough provisions. At the battle of Baghdad in 1733, Nader was defeated by an opponent on par with him, Topal Osman Pasha. Nader learned the hard way that he was not the only military guinness in the Islamic world. Nader was forced into a hasty retreat. The political repercussions were more severe than the military ones, as they showed that Nader was not invincible and that Nader’s heavy tax demands did not always guarantee victory. A provincial revolt against Nader broke out in Persia soon after his return, which he quickly suppressed. Nader decided to prepare for another campaign against the Ottoman Empire despite the rebellion, which shows that Nader’s self-confidence was not broken. Nader raised another army and invaded Iraq again; this time, he did not underestimate his appointment and, as a result, was victorious at the battle of Krikuk, though he had to withdraw back to Persia to deal with a rebellion.

The rise of Nader Shah

In late 1735, Nader decided it was time to become Shah in his own right.Like Napoleon in 1804, Nader approached his goal under the veneer of semi-democratic legitimacy. He arranged a corolla (grand meeting) of all the leading figures in Persia. The gathering “concluded” (by silent coercion) that Nader should become the Shah of Iran. On March 8, 1736, Nader was crowned the Shah of Iran, officially making him Nader Shah as he was now officially known. Again, there was no bloodshed. Nader Shah began his reign by reforming the Safavid’s religious policy. Nader’s religious views are complicated; he had no patience for ritual and intensely disliked much of the Shiite clergy, which had become bloated under Safavid rule (another warning to the current rulers of Iran). Nader Shah rolled back many of the Safavid’s Shia supremacist policies that had alienated Persia’s non-Shia inhabitants. He could, and probably should, have done much more. Nader’s restless character made him well suited to life in the saddle and helped endear him to the soldiery. Unfortunately, it probably made him ill-suited to empathize with city dwellers and farmers, whom he tended to see only as a source of revenue or provisions. On the other hand, Nader acquired a reputation for firm justice, and rather strangely, he was known to respect women and punish rape, even when his troops committed it. Nader Shah also reformed the administrative apparatus to make it more efficient for tax collection. Nader Shah also recognized the importance of commerce and punished banditry severely; he was also friendly towards European merchants despite his incessant demands for revenue. Had his military reforms taken hold, they could have set the foundation for Persia's military and economic transformation. However, that was not the case because, in my opinion, Nader Shah had neglected to reform (among many other things) Persian law.

When Napoleon seized power in 1801, one of the first things he did was start forming a modern civil code of law for France, enacted as the Napoleonic code in 1804, the year of Napoleon’s coronation. The Napoleonic code made people equal before the law regardless of social status, guaranteed the right to legal counsel, and guaranteed the right to private property. The code remains the basis of civil law in France, much of Europe, and the rest of the world. Napoleon wrote during his final exile in Saint Helene that the code was his greatest accomplishment. Had Nader Shah done something similar, Middle Eastern history might have changed. Though Napoleon and Nader look like mirror images of each another, they had very different upbringings. Napoleon was a lawyer’s son and was highly educated; he ruled over a sedentary society, and the ideals of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution provided the foundation for Napoleon’s legal reform. Nader, on the other hand, was the son of ordinary herdsmen and grew up in a part of Persia that was primarily pastoral, far from Persia’s urban centers; he was “educated” in a very martial culture typical of the Nomadic tribes that frowned upon nonmartial professions, particularly “intellectuals” like lawyers. At the time, the Islamic world arguably had no equivalent to an “enlightenment” to provide momentum for extensive legal reform. Therefore, it’s somewhat understandable, but no less tragic, that Nader Shah failed to enact long-term legal and institutional reform to secure his legacy as Napoleon did.

Seeds of destruction

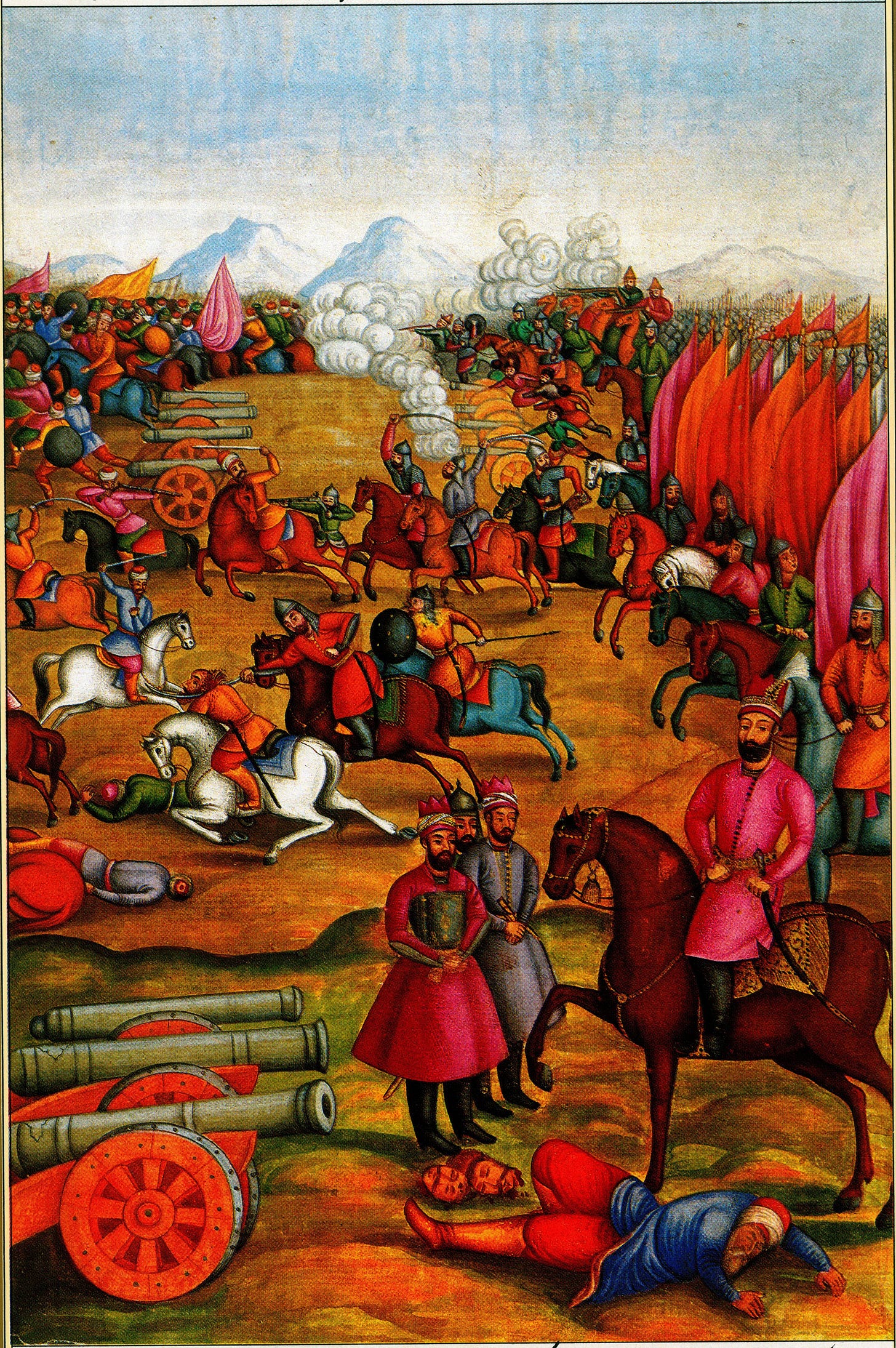

In 1739, Nader Shah set his sights on India, not to conquer but to plunder. Nader was perennially cash-hungry, and India was the most prosperous continent in the world at the time. The Mughal Empire ruled Much of India and comprised at least 100 million people. Persia had a population of between 15 and 30 million. Superficially, it doesn't seem reasonable for Nader to invade India, but actualy he was in a position of considerable advantage. Like the Safavid dynasty, the Mughal dynasty was reaching the end point of Ibn Khaldun’s cycle. It was mired in corruption, factional infighting, revolts on the periphery, provincial governors who were, in practice, becoming independent warlords, and an outdated military. Nader was probably well-informed of the Mughal’s weakness. As he approached India, Nader Shah had masterfully used his army's superior intelligence gathering to locate the Mughal army, possibly ten times his size, but encamped in a position ideally suited for Nader to take advantage of his enemy’s weakness, so he attacked them. At the Battle of Karnal, Nader Shah’s army effectively destroyed the Mughal army. The Mughals were primarily equipped with outdated matchlocks and bowmen; its cavalry consisted of heavily armored horsemen and elephants, which made easy targets for Nader’s artery and his men’s heavy muskets. Nader Shah correctly anticipated that the enemy would try to outflank, and thanks to the topography, he could anticipate where they go and set up an ambush. Casualties on the Mughals casualties were superficially light, but most Mughal commanders riding on Elephants and heavy armored horses had been killed. Their deaths resulted in a complete breakdown of order, and the army disintegrated.

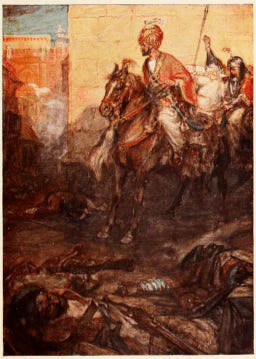

Strictly speaking, only part of the Mughal army was defeated. Ever the pragmatist, Nader Shah decided to secure what he came for in the easiest way possible. Nader lured the Mughal Emperor Mohammed Shah to meet him only to take him prisoner. Under Mohammed Shah’s name, the Persian army marched into Delhi unopposed on the 20th of March 1739. One of the reasons Nader Shah had effectively kidnapped the Mughal emperor was because he wanted to avoid a sack of the city as Tamburlaine’s armies had done 300 years earlier, not out of humanitarian concerns but because he had much more to gain by extracting revenue from Dehli and the rest of the Mughal empire via taxation/tribute. Nader’s somewhat biased views of city dwellers probably made him underestimate the city's reaction to his intentions. It started with a dispute between Persian soldiers and grain merchants that turned into a riot, forcing Nader to do, to an extent, what he had hoped to avoid: mass violence against civilians. The Persian army's crackdown resulted in a massacre of at least 30,000 civilians. Micheal Axworthy, Nader Shah’s modern-day biographer, marks the Dehli massacre as a turning point. Up until that point, Nader Shah had used violence sparingly and avoided mass slaughter. For example, when dealing with the 1734 rebellion, he had the ringleaders executed, but the tribes were deported rather than slaughtered on a mass scale. Though Nader had arguably no alternative but to use brutal or lose control of the city, it set a dangerous precedent for how Nader Shah would deal with unrest. After spending two months in Delhi, Nader Shah began his journey home with unimaginable wealth, enough for him to lift taxes for three years, which was very welcome news for Persia’s exhausted population. Nader was at the height of his power and popularity. Muslim and European traders would bring word of his deeds all over the globe, but it would be short lived.

Tearing out one’s own eyes

The massacre in Delhi probably left a psychological scar on Nader. The slaughter of entire cities had been expected in the time of Genghis Khan and Tamerlane (cities were also less populated), but not in Nader’s time. As previously stated, he had not used violence on a mass scale before. Nader Shah’s physical health was probably under strain as well. Though no alcoholic, Nader was a heavy drinker, typical for a Persian warrior; by 1740, he began to display symptoms that would probably correlate to liver problems. His physical health issues would have reminded him of his mortality, which could have impacted his self-confidence. Nader’s relationship with his son Reza Qoli began to deteriorate. It’s not unusual for Monarchs to have complicated relations with their heirs, but in Persia and India’s case, that often leads to civil war. The Safavid Shah tried to neutralize the potential threat posed by their sons by locking them up in the Harem, which often resulted in them growing up unfit to rule. Nader Shah recognized this early on and often had his son with him during military campaigns; in any case, Reza Qoli was already a grown man by the time his father became Shah. When Nader set out for India, he left his son Reza Qoli to rule Persia in his absence, illustrating his trust in his son.

Reza probably had deep insecurites common in the sons of highly accomplished figures like Nader Shah, which may have driven him in some ways to act impulsively, cruelly, and unwisely. While Nader Shah was on campaign in India, Reza Qoli had the deposed Shah Tahmaseb, along with his family, executed. When Reza’s wife, who was also the former Shah’s sister, found out, she committed suicide. Perhaps more disturbing from Nader’s perspective was his son’s propensity for extravagance, which was on par with the late Safavid’s, which Nader Shah had always loathed. Nader had always been fond of his son, tending to indulge him and overlook some of his actions as youthful impulsiveness, but now his patience was running thin, and his paranoia was growing. Reza’s rivalry with Nader’s chief councilor, Taqi Khan, may have put further strain on the man. The state of Nader Shas’s physical health did not help his mental health. Contemporaries noted whenever Nader Shah had physical health problems, his temper flared. It’s not unusual for despots to behave erratically in response to physical ailments; for instance, Nader’s contemporary Tsar Peter of Russia was notorious for his fits of rage that accompanied epileptic seizures.

For now, Nader was still of sound mind enough to continue his military campaigns, this time against unruly tribes on Persia’s northeastern frontiers, which was met with mixed success. It’s possible that campaigning close to home may been of some comfort to the man. In addition to an increasingly complicated relationship with his son, some of Nader Shah’s closest associates, such as his brother and mother, who had been close to him his entire life, died. Nader Shah may have started to feel lonely and isolated. His next campaign in Dagestan, on the western coast of the Caspian Sea, was also brutal due to the mountainous terrain and damp landscape, which may have affected his physical health. Reza was also becoming paranoid of his father. One account of dubious authenticity says that Reza had asked an archer if he could hit the Shah. The rumor reached Nader Shah, who summoned his son to explain himself, but when Reza Qoli entered his father’s tent, he still had a dagger around his belt, which he refused to remove after being told to hand over all weapons before entering the tent. The incident led to an open rupture in the father and son relationship. Reza denied any wrongdoing but unwisely stated that he suspected his father of planning to kill him. Nader Shah might have forgiven his son if Reza had shown humility and asked for forgiveness, as many of his associates tried to make him do, but Reza remained obstinate. Perhaps reluctantly and reflecting a trend towards violence that had been increasing since the massacre at Delhi, Nader ordered his son’s eyes torn out and brought to him; when it was done, Nader Shah reacted like King Lear and wept “What is a father? What is a Son?” Reza last told his father, “It is not my eyes you have taken out, but your own.”

Descent into Madness and Death

The blinding of Reza understandably shook Nader’s psyche and must have also taken a bitter blow to his self-confidence. Nader’s self-confidence had helped him refrain from acts of excessive cruelty in the past, but now he was losing it. The consequence for Nader was that he seemed to have lost any empathy for his subjects. As previously stated, Nader’s army and wars were expensive. The raid into Delhi enabled him to pay for the Dagestan campaign, but by 1740, that had all been exhausted, and he resorted to even more rapacious taxation to pay for another campaign against the Ottomans in Iraq. From first-hand experience, Nader must have known that rapacious taxation would cause suffering and unrest, but he no longer seemed to care. It was almost as if he wanted everyone to suffer like he was. The consequences were disastrous. One account by Dutch merchants reports that trade in the 1740s had fallen by one-fifth of the level it was in 1722. While laying siege to Mosul in 1743, Nader suddenly decamped and left; one explanation is that there were revolts in Persia and that Nader, a year after blinding his son, lost his energy for sieges.

The most serious revolt was led by Nader’s former favorite, Tagi Khan, which was undoubtedly a further blow to Nader’s state of mind. Tagi Khan seized control of the city of Shiraz in central Persia which had already rebelled against Nader’s tax collectors. Tagi Khan probably underestimated the forces his former master could muster, Nader’s forces besieged Shiraz for four months until the city gave surrendered. Tagi Khan was captured and taken to Isfahan, where Nader had him castrated, blinded in one eye, and forced to watch his sons executed and his wives raped. It’s a common reaction to act violently against a friend’s betrayal, but the extent of Nader’s revenge on Tagi Khan was cruel even by the standards of the time. There are no records that Nader was prone to sadism before, and Nader had a track record of respecting women and punishing rapists. Even more surprising is that Nader did not execute his former friend; instead, he sent him to Kabul as governor. This may have been a more sadistic form of punishment since the proud Afghans would show no respect to the one-eyed eunuch.

Nader embarked on another war with the Ottomans, avoiding sieges. He instead fought another pitched battle with the Ottomans at Kara in 1745 and emerged victorious, concluding a favorable peace treaty with the Ottomans. Unfortunately for Persia, Nader’s emergent paranoia and sadism were out of control. His demands for tax revenue led to more revolt, which he responded to with what had become costumery cruelty. Even in places that hadn’t revolted, Nader often ordered exactions and torchers of accused embezzlers and tax evaders. The Persian Army, forged by Nader, could have become the protector of Persia and the nucleases for Persia’s transformation into modernity, but instead, it became a brutal, oppressive pillager that brought suffering to the very people it was supposed to protect. From the beginning, Nader placed the army's interests above all else, and in return, they served him unflinching loyalty, but by 1747, Nader’s paranoia would break that loyalty.

Nader’s growing Paranoia led him to suspect the Persian officers on his guard, including his own nephew, of plotting to assassinate him. Nader’s forces had usually been composed of roughly equal numbers of Persians and non-Persians, now he was about to shatter they very dynamic that had cultivated. On the night of June 19th, 1747, Nader summoned his Afghan commanders and ordered them to arrest all the Persian guard officers in the morning, since the Afghans owed loyalty to Nader only they could be trusted to carry out his bidding, but word reached Nader’s nephew Mohammad Qoli Khan, who may have realized what his uncle had in store for him and the others, he immediately notified his colleges, and they made the only rational decision to strike first. That night, the rebellious guards burst into Nader’s tent, where he was stabbed and decapitated. They then proceeded to loot Nader’s remaining treasury and harem. Fighting broke out between the Persians and the Afghans. Eventually, the Afghans went home, and the army dispersed.

Nader’s death opened a new chapter of suffering for Persia. Governors across the empire declared their independence. Mohammad Qoli Khan declared himself Shah and ordered the execution of Nader’s surviving sons, including the blind Reza. Eventually, Qoli was deposed and blinded by his brother; later, the two were both executed by a rival warlord. Eventually, by 1789, a new dynasty, the Qajar’s, took over a much-diminished Persia, which now constitutes modern-day Iran. The Qajar’s adopted a policy of isolationism, partly because Persia had been bled dry by decades of war and did not want to risk being overthrown. Though relatively peaceful, Persia under the Qajar’s was also stagnant. There were no attempt at modernization or reform, even as European imperial powers, most notably Britain, which benefited the most from Nader’s sacking of Delhi, were nibbling away at Persia’s sovereignty. Ultimately, Persia returned to the old stagnant status quo, which was the worst possible outcome.

Conclusions

No one will ever know how things might have turned out differently. Nader Shah had already accomplished the extraordinary; he independently created the best army in the world, better than the Europeans at the time. In Europe, military transformation led to economic and administrative transformations beyond tax collection, as previously noted. A Persia with a modern army sustained by an effective inclusive administration that cultivated the economy rather than simply exploiting it could have changed the course of history. A revived Persia could have filled the vacuum in the Islamic world that resulted from the decline of the Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal dynasties. But it was not to be. Nader had displayed some awareness of economics early in his career when he forbade as much as possible the sacking of cities, promoted commerce, and limited the rapaciousness of tax collection. However, there was still so much he should have done or that his successors could have done. Reza proved himself an able administrator in his father’s absence and criticized his father’s excessive war-making. Many expressed hopes that Reza would enact more reforms when he became Shah, but he never got his chance. The story of Nader and Reza is like a Shakespearian tragedy. It’s not unusual worldwide for monarchs to have complicated relations with their heirs. Nader’s contemporary, Peter, the Great of Russia, had his son tortured and executed, yet did not descend into nihilism and insanity like Nader. Regardless of what happened to Nader’s dynasty, his legacy could have been better preserved if he had enacted long-lasting legal and administrative reforms, as Peter had done and Napoleon would do. Ultimately, the only part of Nader’s legacy that survives is that he saved Persia, but even Persia’s post-Nader survival was due to luck. Persia would have been doomed if foreign powers had taken advantage of the turmoil that followed Nader’s death in 1747 to invade Persia as they had in 1722. Popular memory has Reza saying, “It is not my eyes you have taken out, but the eyes of Persia.”