The Battle of Myeongnyang Strait took place off the coast of Korea in 1597 between the forces of the Korean Navy and the Japanese navy. It resembles a cross between the battles of Thermopylae and of the Spanish Armada. The Korean Navy, under Admiral Yi Sun-sin, with just twelve ships, defeated a Japanese fleet of hundreds. The Battle of Myeongnyang Strait and Japan’s invasions of Korea from 1592 to 1598 (the Imjin War) had significant implications on the history of East Asia. Yi Sun-sin, undoubtedly one of the most brilliant naval commanders in history, fought at least twenty-six naval engagements against numerically superior foes and was victorious in them all. His victories helped shape the course of East Asian history.

The battle and Japanese invasion of Korea is not well known outside of the region, partially because there was no territorial change after the war and it took place in a remote location without European involvement. More famous events like the Spanish Armada and Japan’s unification wars have overshadowed it.

Background

I plan to cover the Japanese invasion of Korea in much greater detail in another post, but since the main topic is the Battle of Myeongan Strait and Admiral Yi, I will keep it brief. By 1592, Japanese warlord Toyotomi Hidetoshi had succeeded in unifying Japan after more than a century of civil wars between rival samurai warlords. Hideyoshi planned to use Korea as a stepping stone to conquer China. In a later post I will cover in more detail why Hideyoshi’s vision of a Japanese conquest of China is not as far-fetched as it may seem, but Hideyoshi possessed what was at the time possibly the most battle-hardened and well-armed (with arquebus) military machine in the world. By comparison, the armies of China and Korea were neglected, poorly led, outdated, and undermined. Japanese forces easily outclassed the Koreans and their Chinese allies on land in terms of both equipment and leadership. Nonetheless, no army can ever advance without supplies. One of the reasons naval warfare has played an important role throughout history is because maritime transport is by far the most effective means of large scale logistics. Anyone who controls the sea can ship large amounts of supplies to the forces on land and deny the enemy from doing the same. In the case of the Imjin war, as the Japanese invasion is known in Korea, the man who prevented the Japanese from resupplying their forces was Yi Sun-sin, who by extension altered the entire Japanese war machine.

Yi Sun-sin’s Early Life and Career

Yi Sun-sin was born in Seoul in 1545. It is assumed his family was of modest means since there was no evidence that Yi Sun ever applied for the civil service exams, which required expensive education. So, Yi Sun sought a less glamorous but more accessible military career, for which he was commissioned as an officer at 31. Yi’s relatively advanced age when he started his military career is probably evidence that he had trouble passing the required physical exams. Despite his family’s limited means, Yi likely studied the Chinese military classics whose principles he would apply on the battlefield. He must have also studied accounts of naval warfare by Korean naval commanders. Therefore, it was Yi Sun’s education, not any first-hand experience in naval warfare, which he did not have, that helped forge him into one of history’s most remarkable naval commanders.

Yi’s first fifteen years of military service were atypical for a naval commander; he commanded various garrison forces on Korea’s northern border, where presumably he saw some action against the Jurchen tribes. By all accounts, Yi refused to engage in cronyism and corruption that was endemic in the Korean army at the time; nonetheless, his competence and, perhaps, more importantly, the patronage of his childhood friend Yu Song-nyong, who had become Prime Minister of Korea, kept him from being dismissed. Yi’s only experience in navy command was a brief stint as a base commander in the province of Cholla-do in 1581. As is often the case with Yi, he ran afoul of his superiors, presumably because he refused to engage in corrupt practices and was outspoken against those of his superiors. Again, Yi’s career was saved thanks to Yu Song-nyong's patronage. Though Yi was deeply critical of the corruption often associated with patronage, his career largely depended on patronage. Patronage in various forms is universal and not always a bad thing. Hideyoshi’s meteoric rise started with the patronage of Oda Nobunaga, for example. Yu Song-nyong was perhaps Korea’s most gifted politician, so his patronage of Yi must have been motivated by practical factors, not friendship. On Yu’s recommendation, Yi was appointed commander of the navy forces of Cholla Province on Korea’s southwestern tip. As soon as Yi arrived, he started to whip (sometimes literally) his forces into shape, repair his badly neglected ships, and build new ships and cannon, all of which would prove decisive in the coming conflict.

Japan’s Invasion

Yu’s patronage of the highly competent Yi was an exception. Patronage in the Korean military and bureaucracy enabled corruption and incompetence. The ruling dynasty of Korea, the Joseon, was founded by a military commander who seized power in a military coup. To prevent anyone else from doing the same to them, the Joseon Dynasty initiated a policy of keeping high-ranking officers away from the armies they commanded and of mid-ranking officers appointed thanks to connections with civilian officials. This had the desired effect of making sure the Joseon would face no threats from its army, but it severely weakened the latter’s efficiency. The Korean army was undermanned, with poorly trained peasant conscripts armed with archaic weapons led by generals with limited if any experience in actual combat. On the other hand, the Japanese were led by battle-hardened veterans of Japanese wars. Japanese armies by 1591 were primarily composed of peasant conscripts armed with arquebuse muskets and spears. Katanas armed Samaria mainly filled the roles of officers and generals. The corruption in the Korean military extended to the navy as well. When the Japanese invasion began, the commander of the naval forces in Pusan, Won Gyun, panicked and scuttled his fleet of 200 ships without a fight.

A less able commander than Yi would have panicked or sought to lash out when hearing of the catastrophes that befell Korea in the first months of the Japanese invasion, but Yi kept his cool. He knew that his forces were not ready, and he knew better than to go headlong without any intel. Instead, he focused on training his men, repairing his poorly-managed ships, and gathering intel on the enemy. At the same time, he was gathering as much information as possible on the topography and currents of Korea's western coastline. Commanders who engage the enemy on grounds or waters they are familiar with tend to have the advantage, as was the case with the Spanish Armada. The intel on Korea's coastline would later play an instrumental role in the Battle of Myeongnyang. Yi gathered crucial intel from eyewitness accounts of the Japanese fleet and carefully planned his first foray into battle. Yi probably learned from accounts of naval engagements against Japanese pirates that the Japanese were far behind the Koreans in terms of cannon technology,

Opposing Forces

Before the Industrial Revolution, no two ships were the same size and shape. Shipbuilders had to design individual ships based on the quality, quantity, and shape of the wood they had. Korean and Japanese ship designs were very different from Western European gallons. The primary warship of the Korean arsenal was the Panokson, or roofboard ship. It was about 25 meters long, powered mainly by oars below deck. The upper deck was enclosed by high walls that offered the men some protection and a castle-like structure in the center of the ship, where the captain or admiral could issue commands and have a good vantage point. Korean warships had large-caliber cannons designed to sink enemy warships. Japanese ships at the time were superficially similar in appearance but very different. Japanese warships had no heavy cannon that could penetrate the hulls of Korean warships. It's possible that some Japanese ships may have possessed some light cannon, which could not penetrate a wooden hull except possibly at point-blank range. Japanese ships had one bunch of sculling sails to the Koreans’ two, which gave the latter much more speed and maneuverability. Although ships played a vital role in resupplying Japanese armies, especially during Hidetoshi’s subjugations of Shogaku and Kyushu, naval warfare did not play a prominent role in Japanese warfare. In most cases, it was treated as an extension of land combat, where the intent was to board the enemy and engage in hand-to-hand combat.

Yi and his chief shipbuilder, Na Tac-young, devised a solution to negate the Japanese advantages in close quarters combat and small arms: the Kobuk son or Turtle Ship. What set the turtle apart from any other ship was that it had a roof over its main deck that prevented it from being boarded and protected its crew from enemy fire. The Koreans first used such ships in the early 15th century against Japanese pirates. By 1591, they had fallen out of usage. Still, Yi must have learned about them by researching the history of Japanese piracy and correctly recognized how useful it could be against an enemy whose strategy revolved around boarding. The turtle ship has popularly been depicted as iron clad, but that is highly unlikely. It was unnecessary since the Japanese had no cannons and thick wooden hulls to protect against arquebus fire. Yi would have prioritized iron for the construction of cannons and cannon balls (or darts). Turtle Ships probably had iron spikes on their roofs to prevent boarding. The turtle ship's advantage was that its roofed hull protected it from Japanese musket fire and boarding, effectively neutralizing the only way the Japanese knew how to wage war at sea.

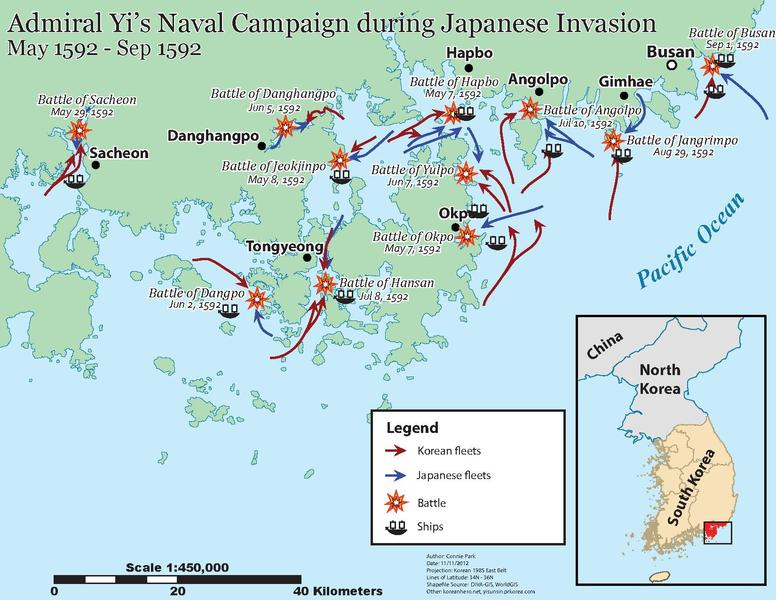

The Navy Strikes Back

Yi engaged and destroyed several Japanese fleets off the islands of Geoje and Hansando with almost no losses on his side. Yi’s preferred tactic was the “crane wing formation,” which involved enveloping the enemy fleet in a semicircle to be felled by cannon fire. Yi preferred to engage the Japanese in waters close to islands; that way, any Japanese sailors that were ashore would have no means of escape and could be slaughtered on land. This was standard practice at the time; the English treated shipwrecked Spanish sailors the same way ten years earlier. In one instance Yi was wounded by land-based musket fire. Even wounded, Yi continued to fight, which galvanized his men even further. Yi cultivated what would perhaps become his most important weapon: his reputation.

Yi’ success threw all of Hidetoshi’s plans into turmoil. The Japanese needed access to the Yellow Sea to keep their advancing armies supplied. Without supplies, the Japanese could not sustain their advance. The Japanese response was hampered because they had no unified command system. The Japanese “navy,” like its army, was a feudal force consisting of ships under the command of various Daimyo (feudal lords), mainly from Kyushu, many of whom were former pirates or the literal descendants of pirates. There was little to no cooperation between them or with the Japanese armies on land, who could have attacked Yi bases but did not attempt to do so until it was too late. Hidetoshi was the only person with authority over all Japanese commanders, who could not leave Japan for political reasons. In contrast, Yi had command over all Korean navy ships in the Yellow Sea. The news of the Yi-Sun’s success boosted the morale of the Korean royal court, which was hovering on the edge of despair after being forced to abandon the royal capital of Seoul. On the other hand, though Yi was undeniably a skilled military commander, he was no courtier. Yi’s outspoken criticism of the faults of his superiors, though justified, made him undue enemies that made it hard for the court to reward him or listen to his advice. It also made him enemies of politically influential men who could harm him.

Stalemate

Although Yi-Sun's successful defense of the Yellow Sea made a Japanese advance unfeasible, the Japanese armies managed to make it as far as Pyongyang. The royal court asked the Ming Dynasty for assistance. The Ming court decided to send an expeditionary force to Korea’s aid, though its military was suffering from the same deficiencies as the Koreans’. Despite outnumbering the Japanese by a factor of three, the Chinese were unable to dislodge the Japanese forces from Pyongyang. The Japanese commander, Konishi, only withdrew because he did not have enough provinces to survive a winter and because no supplies were coming, thanks to Yi. The Japanese encountered another unexpected problem. Hideyoshi’s strategy was to subdue an enemy with overwhelming force, then recruit the beaten foe into his hegemony. That strategy worked well against the warlords of Japan, but there were no warlords in Korea to subdue. Furthermore, few Japanese spoke Korean and vice versa, so the quality of collaborators was very limited. Many Korean scholar-officials organized guerrilla bands to prey on Japanese supplies. By the time the Japanese decided to attack Yi’s base, the Koreans fortified the mountain passes leading into Cholla province, which the Japanese could not overcome.

Yi’s final action in 1591 was to launch an assault on the Japanese base at Pusan. On the way to Pusan, he destroyed several Japanese fleets at Okpo, Tangpo, Tanghangpo, Anglopo, and Hansan Island; by the time they reached Pusan harbor, at least 400 Japanese ships were at anchor. The ships left were mostly transport ships. Furthermore, the Japanese were by now terrified of Yi and refused to set sail. The only resistance in Pusan came from land-based forces, which, as usual, were ineffective against ships out at sea. Yi succeeded in destroying at least a quarter of the Japanese ships at anchor and losing none of his own. Yi decided against destroying the enemy fleet because he probably did not have enough ammunition, and he wanted the Japanese to leave Korea, not remain trapped in Korea. If Yi cut off the Japanese from Japan completely, they would ravage the parts of Korea that had not been affected by the invasion so far.

Japanese commanders decided to abandon Seoul rather than try to defend it against the combined Chinese and Korean army, presumably due to supply issues. Denied access to a supply route by sea and faced with guerrilla attack overland, the Japanese withdrew to Busan by 1593, where they would be better supplied and better defended against Korean and Chinese counterattacks. The Korean forces, including Yi’s navy, also suffered from supply shortages despite aid from Ming China. The Japanese invasion had shattered Korea’s economy. The invasion devastated or cut off many rice-producing areas in Korea. Yi had to disband at least half of his forces so that they would return to the rice fields to stave off famine in Cholla province.

Failed Negotiations, Factional Infighting, and Disaster

Once reestablished in the ruins of Seoul, the Korean government returned to factional infighting. In Japan, Hideyoshi, seeming to realize that a conquest of Korea, let alone China, was no longer feasible, decided to negotiate a face-saving agreement to end the war. The Chinese and the Koreans wanted the same, but each side’s version of a face-saving measure was incompatible with what the other had in mind, leading to a complete breakdown in negotiations by 1597. Hidetoshi decided to launch a second invasion, presumably with the more modest goal of securing Korea’s southern provinces for Japan, so that Hideyoshi could reward his followers. The Korean court was informed of the Japanese invasion fleet and ordered Yi to attack it before it reached Korea. For reasons that remain obscure, Yi failed to carry out the order to attack the invading Japanese fleet. He possibly believed it was a trap, or that his forces were depleted by disease, or a combination of both. Whatever the reason for Yi’s disobedience, it galvanized his enemies at court, who pressured the King to relieve him of command. The man chosen to replace Yi was the worst possible candidate: Won Gyun, the admiral who scuttled his fleet without a fight at the start of the war.

Won was Yi’s opposite in almost every war. Yi was disciplined and resourceful, though not a politician. Won was cowardly and erratic but a cunning politician who used factionalism at court to defend his position. Unsurprisingly, discipline broke down as soon as Won took command; his erratic behavior and alcoholism made matters worse. While the Korean navy was deteriorating, the Japanese were improving. Hideyoshi reorganized his fleet under a single commander to avoid the rivalries between the former pirate lords that had paralyzed it during the first invasions. The commander of the Japanese forces, Konishi Yukitata, organized an ambush. Konishi lured the Korean fleet to Kadoc island; when the Koreans went ashore to fetch water, they were ambushed and slaughtered by land forces lying in wait. The incident further destroyed the Korean fleet’s morale. Won then led his fleet to the Strait of Choeollyang, where he descended into alcoholism. While their commander’s incompetence paralyzed the Koreans, the Japanese navy launched a well-coordinated assault in dark of night on the unprepared Koreans, boarding ships and slaughtering anyone who washed ashore. Won was certainly killed in battle, though the manner of his death is uncertain. By the end of the day, only twelve Korean ships had remained.

Overwhelming Odds

News of the disaster dismayed the Korean government. It was all the more shameful because Won’s incompetence was already well-known before he was given command. The court did the only practical thing and restored Yi to his former command. Yi returned to his old post in September 1597 to find that his command was only twelve ships against at least two hundred Japanese ships, some of which were armed with captured cannons. The odds would have been impossible for most, but Yi was not like most. First, Yi worked to restore the morale of his badly shaken forces. It may be remembered that Yi faced a similar situation at the start of the war; he had experience lifting morale. Yi’s small fleet was able to move much more quickly than the much larger Japanese fleet, especially among the small islands of Korea’s southwest coast. Avoiding the Japanese main fleet at first, Yi engaged some Japanese scout ships in a series of inconclusive engagements until he found the Strait of Myeongnyan.

Myeongnyang Strait is a thin passage between Chin Island and the mainland, twenty-five meters at its narrowest point, which the Japanese fleet would have to pass through if it was to reach the Yellow Sea. In that era, oceanic navigation was still in its infancy, and errors in navigation were widespread during long sea voyages. For example, in 1628, the Dutch merchant Ship Batavia, heading for a Dutch trading post (also named Batavia), now the modern city of Jakarta, ended up shipwrecked on the coast of Western Australia 2,577 km south of its destination. The Japanese fleet may have been able to cross from Kyushu to Busan, but coordinating a large fleet across the ocean for a prolonged period would have been impossible. Therefore, the only route into the Yellow Sea for the Japanese fleet was off the coast of Korea, through Yi San-Sen and the strait. On the surface, the situation was similar to that of the Spartans at the battle of Thermopylae 2,077 years earlier, where the Spartans and their allies held out thanks to the narrow pass until the Persians found a way around them. Yi was not interested in making a last stand; he was fighting to win.

Yi-San had no doubt never heard of Thermopylae. Still, the Chinese classics mention the advantage of fighting a numerically superior foe in areas where the local topography prevents the enemy from surrounding you. Yi noticed that at certain times of day, the waters in the strait rushed outwards with considerable force. Yi planned to engage in the narrow strait where the Japanese could not deploy their entire fleet against him when the tides pushed with full force. The night before the battle, Yi paraphrased a quote from ancient Chinese military scholar Wu Qi to his captains, “He who seeks his death shall live, he who seeks his life shall die, If one defender stands watch over the gateway can strike terror into the heart of the enemy of ten thousand.’ Yi may have hoped that his men would find the morale to fight and win if they had their backs against the wall. It is also extremely likely that he counted on his own repudiation to affect the morale of the Japanese. Yi-San remained undefeated with a track record of defeating numerically superior foes. There is every reason to believe that the Japanese remained in awe of him, and Yi would prove they were right to be.

The Battle

When the Japanese fleet arrived on October 25, 1597, Yi enticed his foes with a lone flagship. He lured the Japanese fleet into a position where their superior numbers became a liability in the narrow strait, severely restricting their mobility as Yi planned. His “Turtle” flagship led the handful of Korean ships out of a hidden cove to engage the Japanese fleet. As Yi had hoped, the desperate situation galvanized his men to fight with near superhuman resolve, blasting at Japanese ships at point black range. The Japanese had been taken completely by surprise, and though they had experienced ambushes before, they did not think that twelve ships could be a meaningful threat. One of the first Japanese ships to fall was the flagship and the Japanese fleet commander Kurushima Michifusa; his corpse was discovered floating near Yi’s flagship and was identified by an ex-Japanese sailor who now fought for the Koreans. Yi, realizing the psychological value he was given, ordered the corpse decapitated and the head placed at the front of his ship to demoralize the Japanese even further. Finally, the (literal) tide turned in the Korean’s favor, forcing the Japanese fleet back from where they came and amplifying the striking power of the Korean ships. The morale of the Japanese fleet broke, and they turned around to flee into the open sea; Koreans pursued until exhaustion and Yi cautiously halted them. Yi knew better than to push his luck. Thirty-one Japanese ships had been destroyed, many more were damaged, without the loss of a single Korean ship.

Though Yi had to withdraw from the Strait soon after, Yi had accomplished his strategic objective. The Japanese never attempted to sail into the Yellow Sea again and, by extension, gave up any hope of advancing north. The battle secured Yi’s place, albeit one overlooked in Western historiography, as one of history's most formidable naval commanders. His courage, resourcefulness, and charisma managed to turn a desperate situation around. Luck and psychological warfare also played their part. If the twelve ships had not escaped Cheolyong, Yi would have had no ships to fight with. The Japanese remained far behind the Koreans in cannon warfare despite their efforts to introduce heavy-caliber cannons onto their ships. Yi managed to ambush the Japanese, quickly destroying several Japanese ships at point-blank range, including the Japanese flagship and its commander. The loss of their commander, the ferocity of the Koreans, the force of the tides, and the awe the Japanese still felt toward Yi broke their resolve. Had the Japanese kept their nerve or tried to attack again when the tides turned, Yi’s forces would have been overwhelmed by sheer numbers. It’s not something anyone would want to emulate except as a last resort, which it was.

A month after the battle, an incident revealed a dark side of Yi-Sun Sin. Yi received word that his youngest son, Myon, had been killed in a Japanese raid at his family home. This news sent the admiral into a deep depression; he began to have dreams of his son crying out for vengeance. (The official record says Yi started having dreams before word of the raid reached him, but I think that’s apocryphal.) Dreams were considered essential portents in Korean society at the time. Yi’s officers, desperate to restore their commander’s spirits, had a Japanese prisoner brought before him, claiming this must have been the man who killed Yi’s son (200 kilometers away). Yi had the unfortunate man tortured until he confessed. It is common sense universally that a confession obtained under torture is unreliable; this would have been obvious to an intelligent, educated man like Yi. Nonetheless, Yi had the unfortunate prisoner skinned alive. For all his many accomplishments, Yi was still a human being with a very human need to hold someone responsible for the harm that was done to him personally. It should also be noted that cruel and sadistic forms of punishment were universal at the time.

Aftermath

Yi-Sun Sin spent the next few months rebuilding his fleet to launch offensive operations alongside the Ming Chinese Navy. Despite the combined Chinese-Korean forces on land and sea, they failed to dislodge the Japanese from southern Korea. Different priorities between the Chinese and Korean commanders hampered the Sino-Korean war effort. Hideyoshi died on September 18, 1598. On his deathbed, Hideyoshi ordered his armies to withdraw from Korea. The Chinese were content to let the Japanese do so; the Koreans wanted to inflict as much damage as possible. Yi San Sin died after being hit with a stray musket ball in one final battle against the withdrawing Japanese in the Noryang Strait. It is perhaps fortunate that Yi died when he did. Once the Japanese withdrew, there would have been nothing to protect Yi from his enemies at the Royal Court. His friend and patron, Prime Minister Yu, was removed from his post shortly before. In death, Yi received far more recognition from the Royal court than he ever had in life.

Impact and legacy

Hideyoshi probably did not start the second invasion to conquer Korea as he had his first. He intended to “punish” the Koreans for not accepting his conditions for a truce and gain more territory to bargain with. Even if Hideyoshi had accomplished the goals of his second invasion, the Japanese would have likely withdrawn from Korea eventually. Nonetheless, the eventual withdrawal would have been more time-consuming and with a more significant loss of life on both sides. Yi-San’s earlier battles during the first two years of the war saved Korea. The Battle of Myeongnyan Strait probably did not alter the outcome of a Japanese withdrawal from Korea. Still, it helped prevent further loss of life.

Yi is not well known outside of Korea due to the relative obscurity of Japan's invasion of Korea. In both North and South Korea, Yi is considered a national hero and symbol of Korean independence; numerous memorials and films have been made around him. Ironically, Yi is most venerated outside of the two Koreas by Japan. Japanese admiral Togo Heihachirō, hero of the Battle of Tsushima, once responded to a reporter’s comment that comparing him to Admiral Nelson and Yi Sun-sin by saying that no man could ever compare to Yi Sun-sin. Togo belonged to an old Samurai family that served the Shimazu clan, whose ships and warriors clashed with Yi San-Sin. More than 300 years after Yi’s death, he was still held in awe by his old foes.